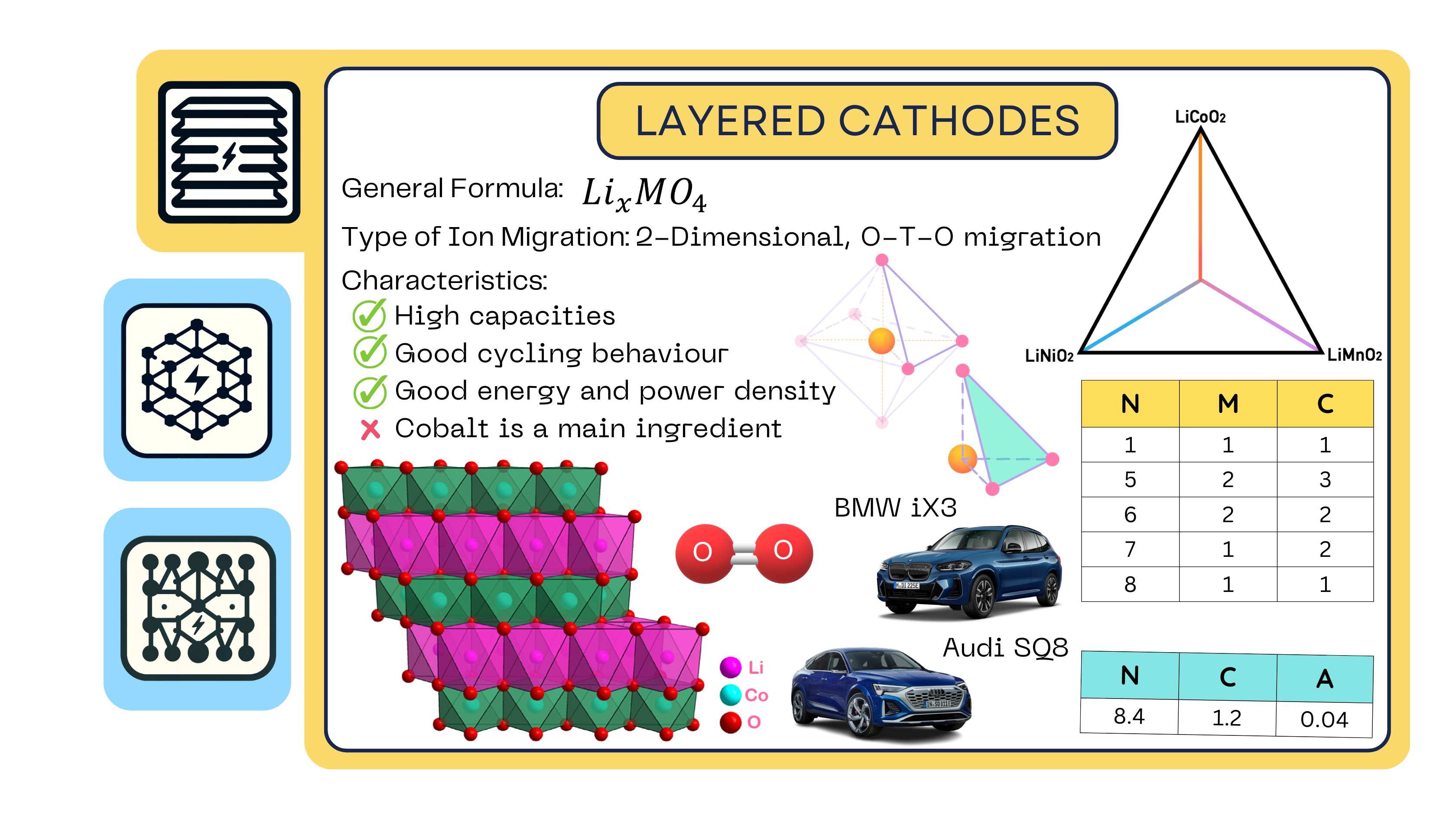

Layered Cathodes

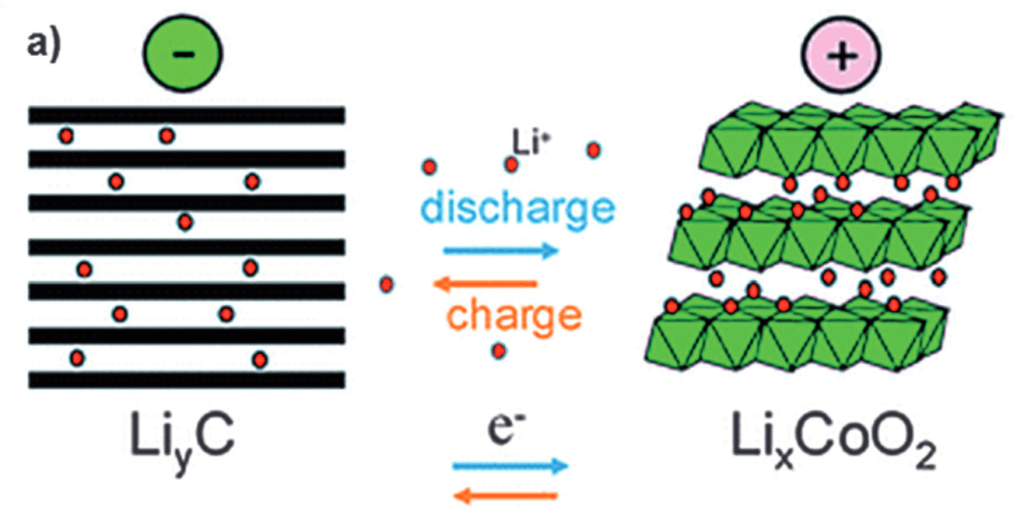

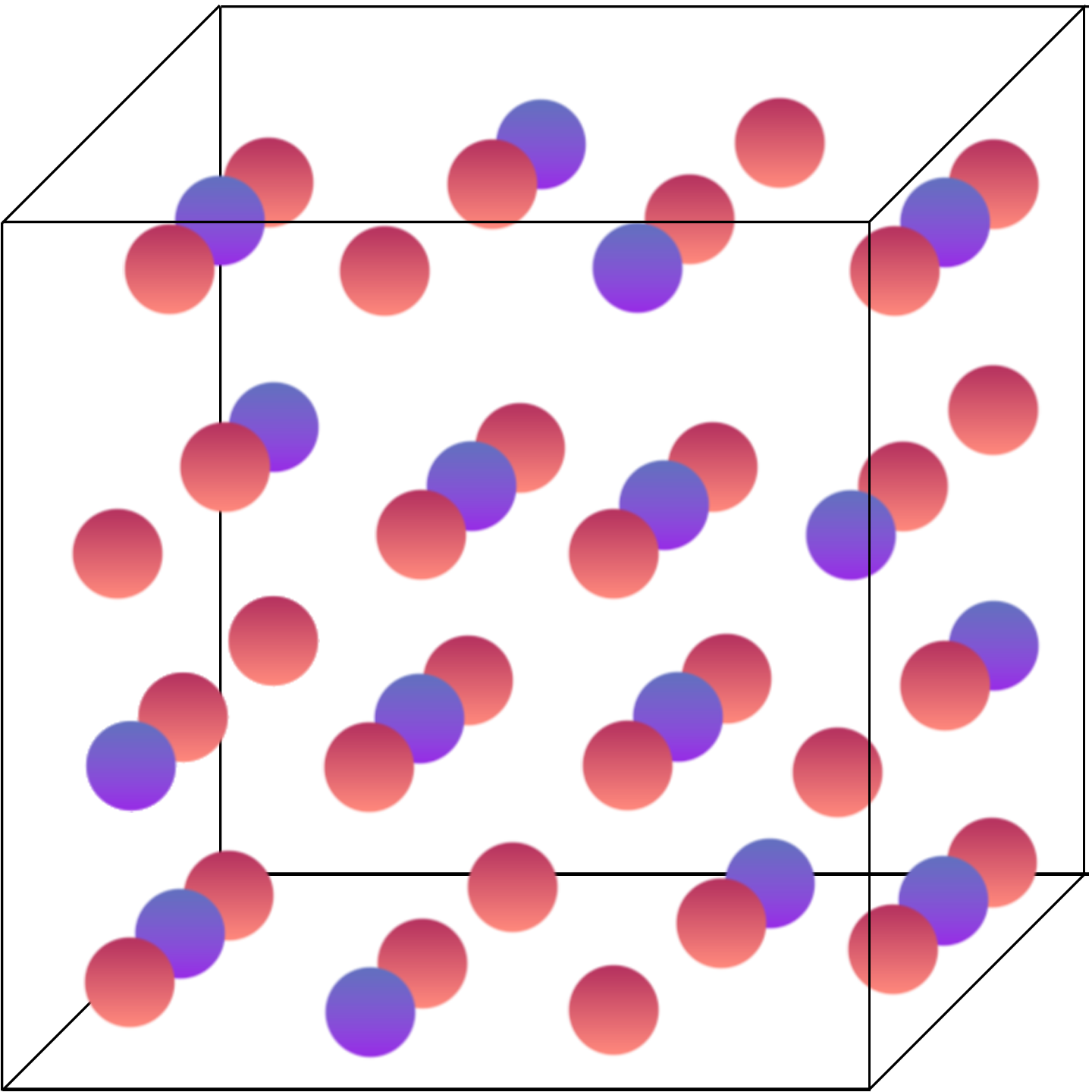

Layered oxides are the most common type of commercialized positive electrode material. These structures consist of a cubic, close-packed array of oxygen anions together with a transition metal. The organization of the transition metal determines the diffusion pathway of the lithium ions. This process is known as intercalation (or de-intercalation) of the positive charges inside the cathode.

For batteries to function efficiently, the intercalation of the ions inside the electrodes must be maximized: the more ions that can be inserted into an electrode, the more capacity the battery will have. Similarly, if the ions can exit the electrode very easily and leave it virtually untouched, the electrode can continue operating efficiently, thus allowing for a better and durable battery performance. The intercalation process can be best observed in the following diagrams:

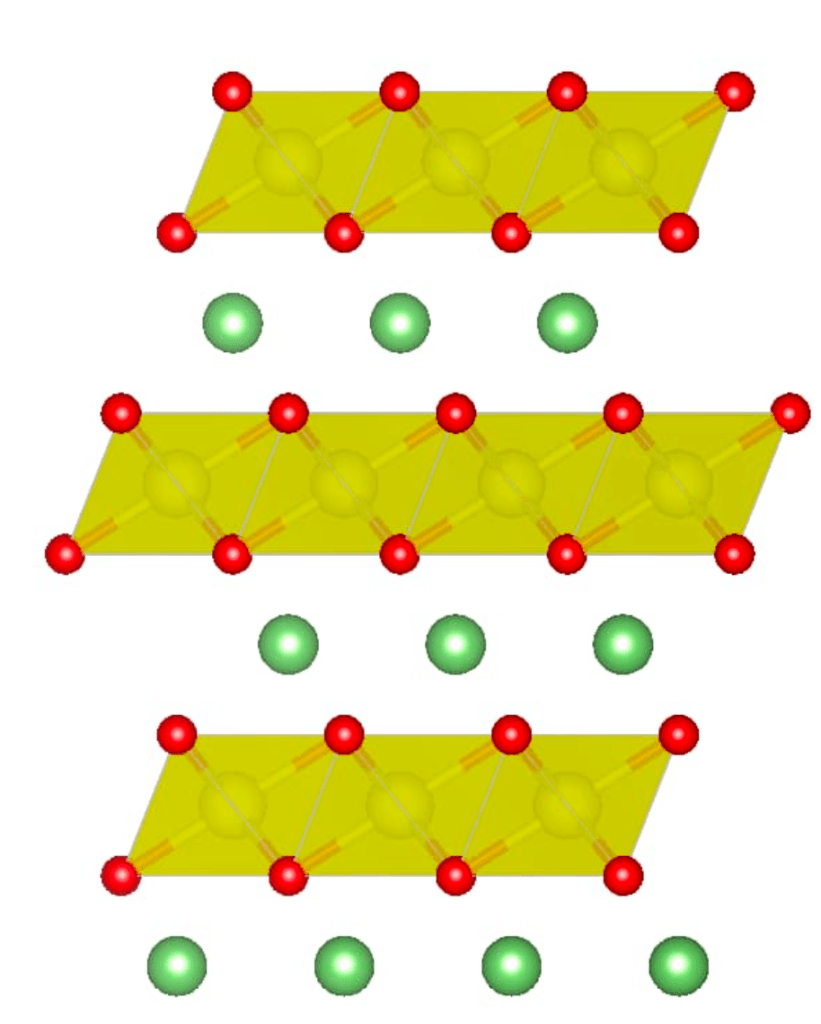

If we zoom into the cathode, we can see it looks like this:

The spaces where the ions move in and out are known are interstitial spaces. These interstitial spaces are not normally part of the crystal structure and are additional to the regular lattice sites. The geometry of the atomic bonding generates interstitials with different shapes, and thus, allows for different types of lithium-ion intercalation. In this case, there are two types of interstitial geometries:

- Octahedral Interstitials: These sites are formed when six atoms or ions surround an interstitial site, creating an octahedral geometry. In this case, two pyramids are base to base, with the interstitial site in the center. In a crystal lattice, this octahedral site is typically larger and can accommodate larger ions.

- Tetrahedral Interstitials: These sites are formed when four atoms or ions are positioned around an interstitial site in a way that creates a tetrahedral geometry. This is like a pyramid with a triangular base, with the interstitial site at the center. Tetrahedral sites are usually smaller than octahedral sites.

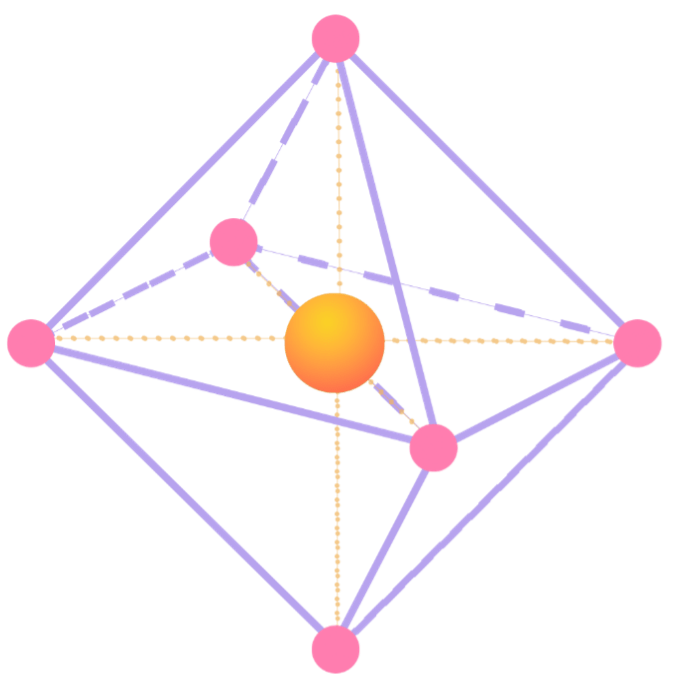

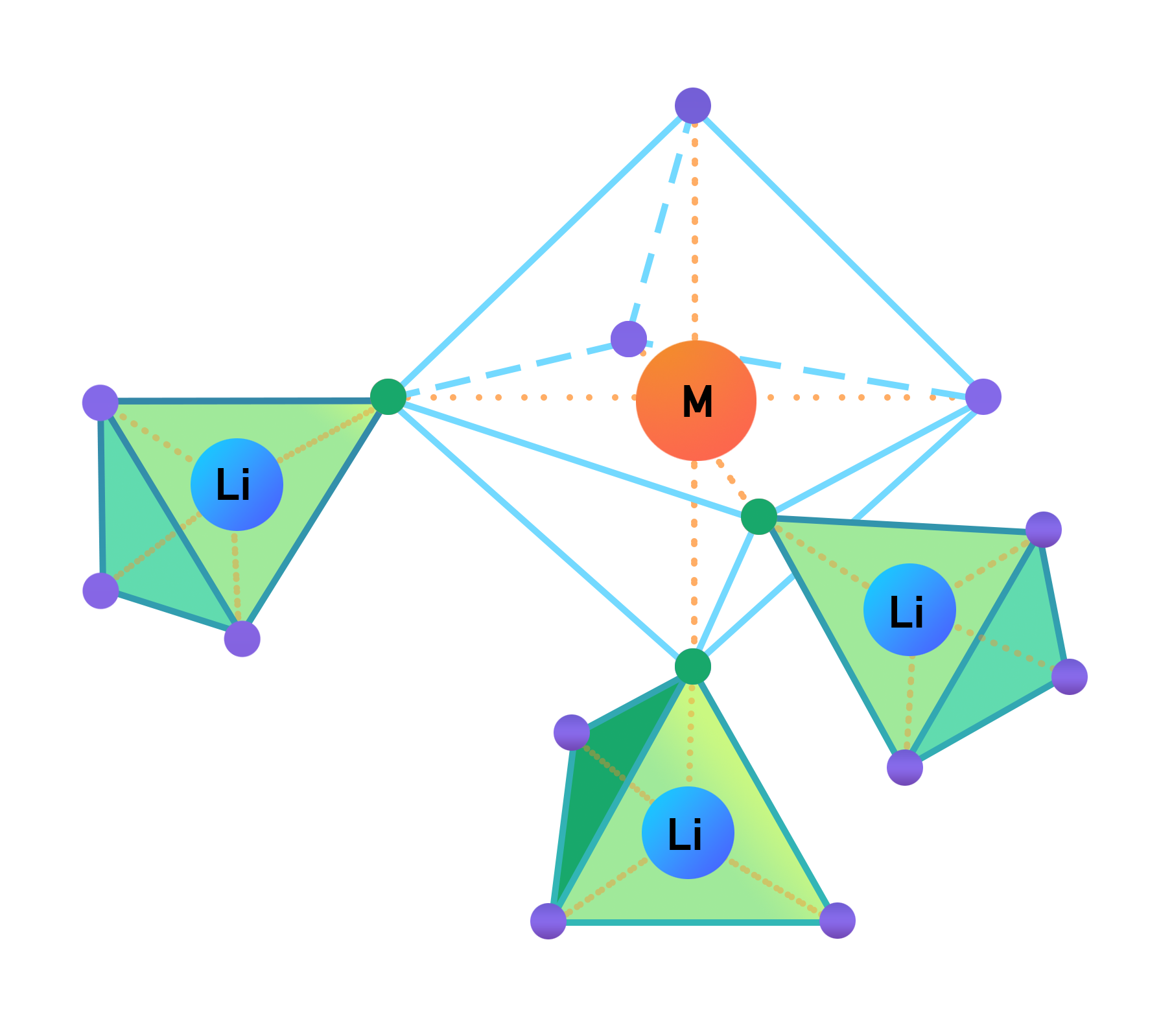

The octahedral and tetrahedral interstitials can be observed in the following figure. The octahedral geometry is obtained when the six oxygen atoms (represented by the pink spheres) align around the transition metal, which, in this case, is cobalt (represented by the orange orb), thus forming the shape with eight faces and six vertices. The atomic bonding of the cobalt with the oxygen atoms is denoted by the orange lines, while the shape of the octahedral itself is highlighted by the purple lines.

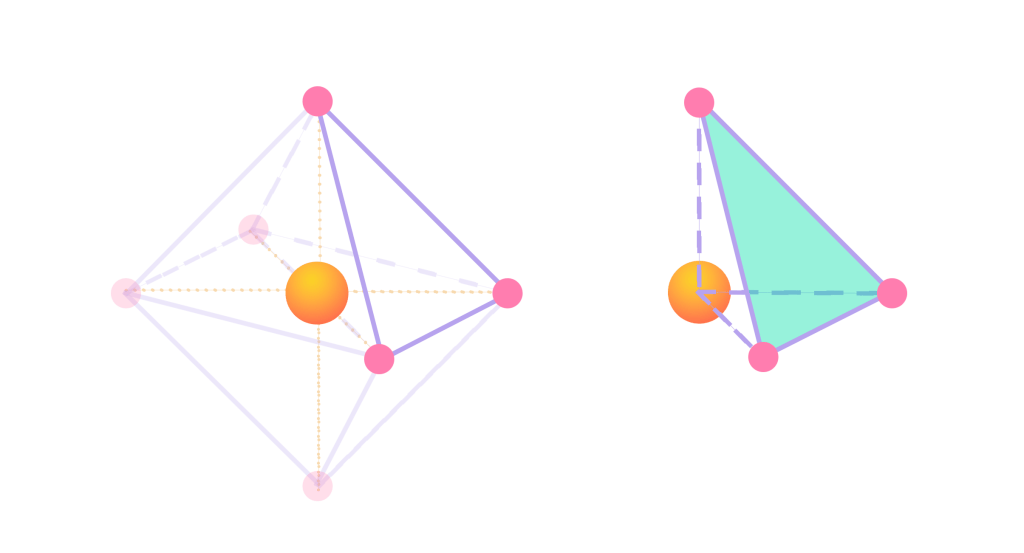

The inside of this geometry can also be further analyzed. In the following figure, a piece of the previous octahedral has been highlighted and dissected. It can then be observed how the cobalt ion forms a tetrahedral shape with three of the oxygen atoms. Therefore, it then becomes evident how there are eight tetrahedrals inside the octahedral. These tetrahedral sites are not occupied, but they sit in between the octahedral sites. They are the diffusion bridge between the interstitials: the face of the tetrahedral that is highlighted in green is where a lithium ion can move throughout the lattice in the electrode.

Although the lithium ion can move in two planes, it cannot move upwards (in other words, in the third plane) because the transition metal is blocking it. For this reason, it is said that layered oxides allow two-dimensional ion diffusion.

Problems with Layered Cathodes

Volume Changes

Layered cathodes do not come without their intrinsic, structural problems. After many cycles of lithium ions intercalating and de-intercalating, they manage to alter the arrangement of the layers that surround them. When the lithium ions exit the structure, the gap they leave in between the layers causes the oxygen anions in parallel layers to be in electrostatic contact with each other. The strong negative charge of these anions produces a repulsion that the atoms themselves will then try to prevent by shifting. This means that the layers rearrange themselves so that the distance of their oxygen ions is now maximized.

However, this reordering causes the volume of the electrode to change, and this can cause the structure to crack. The transition metal can also end up migrating down into the interstitial space (where the lithium ion is supposed to be) in order to minimize the negative anion repulsion. This can result in the formation of disordered rock salt structures that are irreversible and that entail a loss of the active electrode material.

At very high potentials, numerous reactions can occur between the electrode and the electrolyte which can result in the formation of parasitic compounds. These compounds can end up forming a deposition layer on the cathode, which inhibits lithium insertion and de-insertion and can also cause the volume of the electrode to change, effectively cracking it.

Lithium Loss

As the lithium ion is migrating through the octahedral faces of a layered cathode, it might get caught in a bottleneck, which would cause material loss and a diminished capacity.

Oxygen Release

If large quantities of lithium are extracted at a very high rate, the structure may become unstable, causing the oxygen to be released. Lithium cobalt oxide is particularly vulnerable to this unwanted reaction.

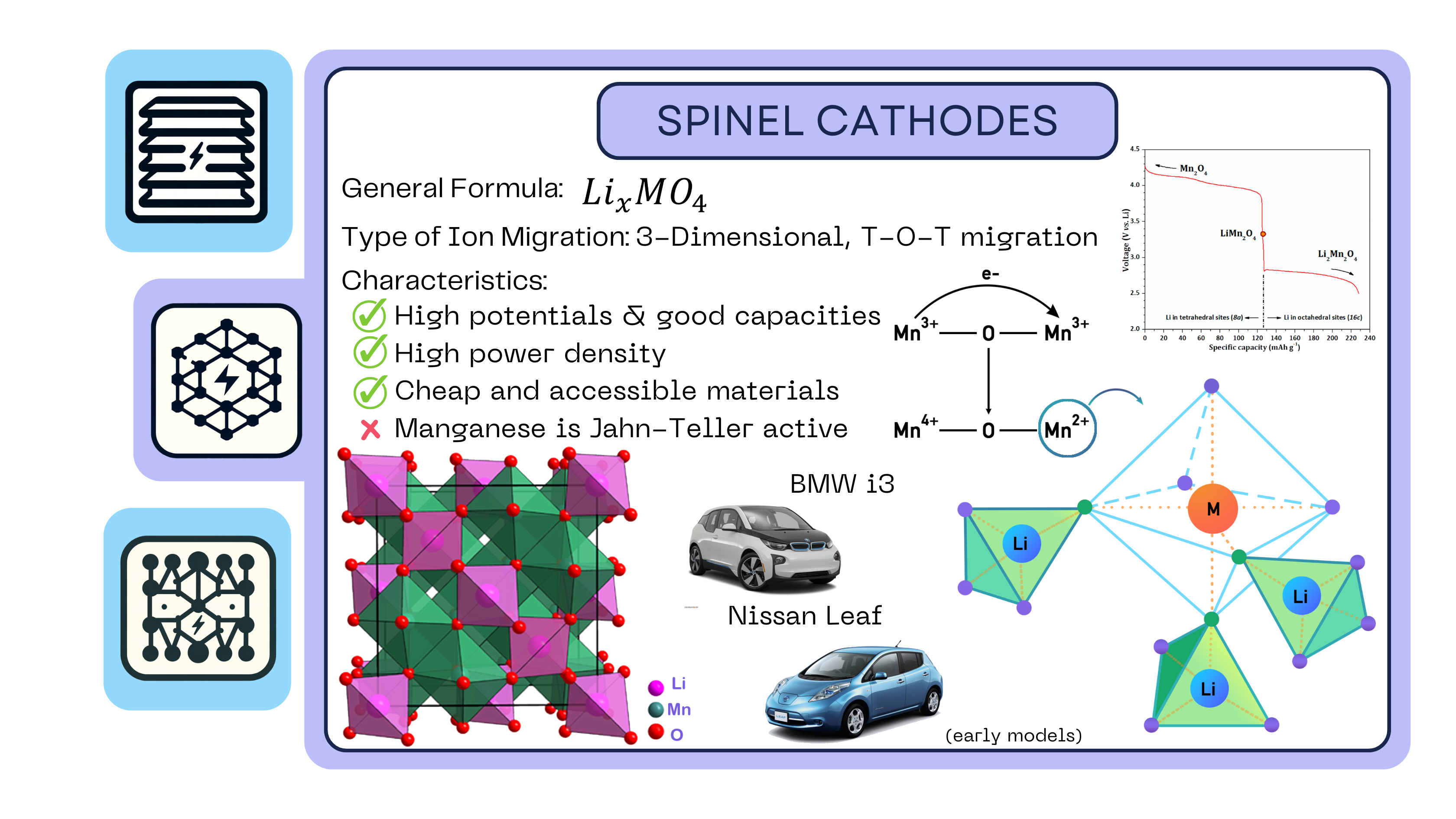

Spinel Cathodes

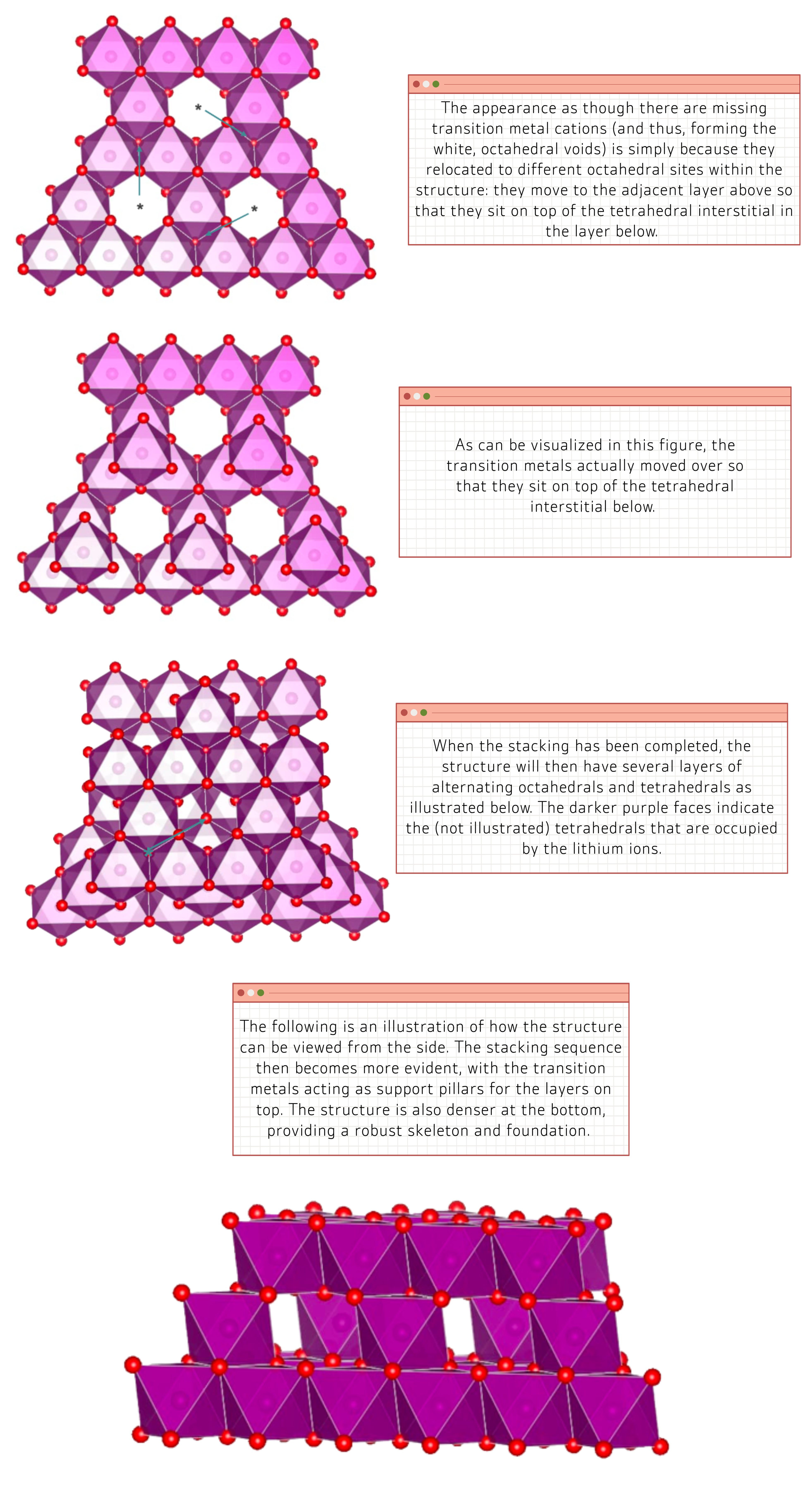

The term “spinel” refers to a specific type of crystal arrangement of atoms, named after the mineral spinel (MgAl2O4), which is the archetype for this structure. In the context of lithium-ion batteries, the most common spinel cathode material is lithium manganese oxide (LiMn2O4). Spinel cathodes consist of a cubic, closely packed array of anions that also have the octahedral and tetrahedral interstitials like the layered cathodes. However, rather than being in sheets like layered cathodes, they are organized in alternating sites within the cube, as observed:

In this arrangement of transition metals and oxygen anions, the oxygen is represented by the red spheres and the transition metal is represented by the purple spheres.

This brings about an alternating geometry of octahedral and tetrahedral shapes, which can be better visualized in the following illustration:

In this diagram, the transition metal is identified by the orange sphere, the lithium ion, by the blue sphere, while the oxygen anions are represented by the smaller, green, and purple orbs. The bonding between the atoms is represented by the dashed, orange lines, while the geometries that are formed are denoted by the blue lines. The octahedral geometry is symbolized by the green lines and the tetrahedral geometry, by the navy lines. Note again that these lines do not exist and are mere visual representations of the geometrical structure of the atomic bonding.

The following figures are a bird’s eye view of the spinel arrangement. They are displayed in a sequential manner, with the first image representing the bottom layer of the structure, and the subsequent images demonstrating how the stacking of the atoms occurs on top of the initial layer:

With spinel cathodes, there are fewer sources of resistance because the transition metals are further away from the octahedral faces, as compared to the layered scenario (lithium ion faces electrostatic resistance from the metals as they are both positively charged).

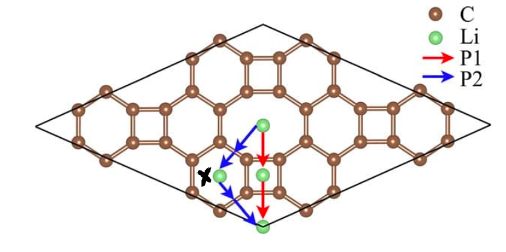

Tetrahedral migration is particularly beneficial as it facilitates lithium migration. This point is illustrated by the following diagram, which depicts two possible migration pathways across a lattice:

If lithium were to follow the blue lines, it would be surrounded by six carbon atoms, where it would sit very comfortably due to preferable six-bond coordination. Being essentially pinned down by the anions would mean the lithium ion would need more energy to overcome the energy barrier that would allow it to continue migrating.

Problems with Spinel Cathodes

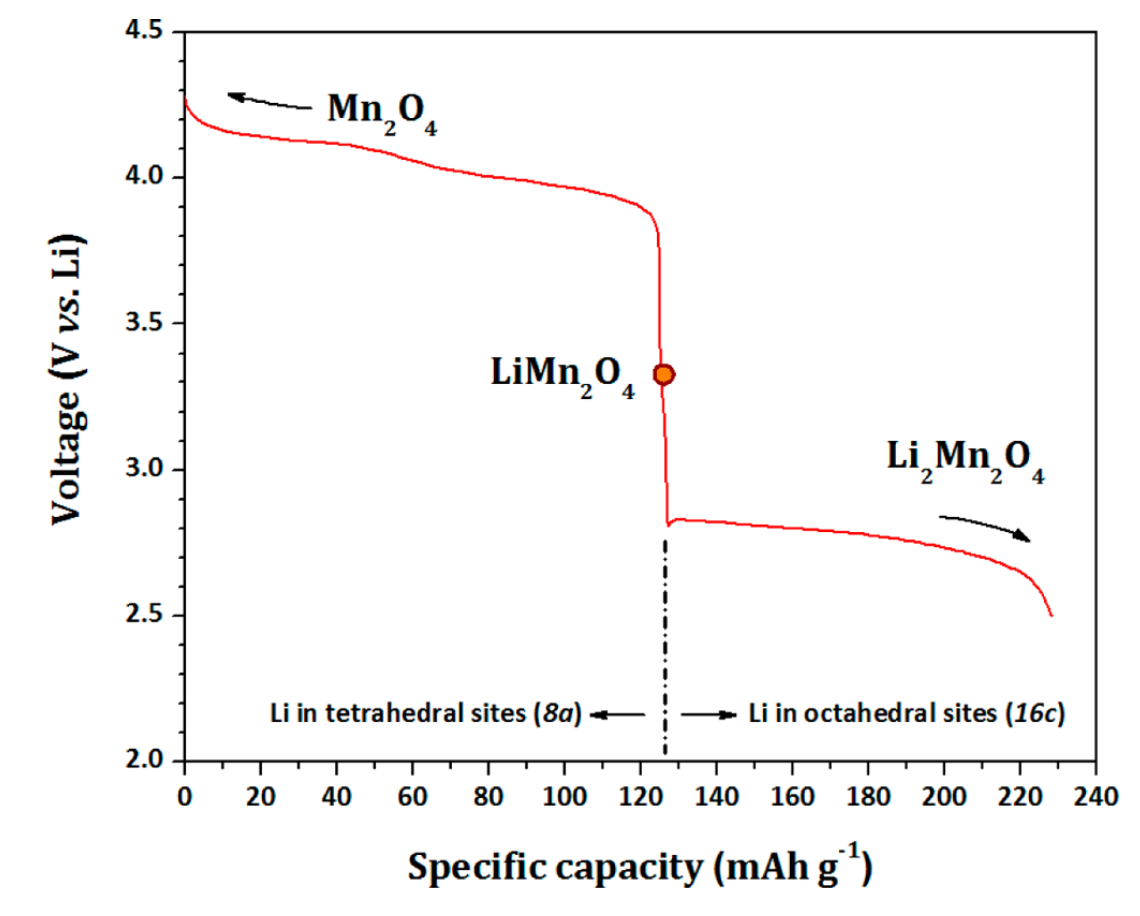

The manganese oxide spinel is particularly sensitive to the stoichiometry of lithium ion. The chemical formula for this material is Li2xMn2O4. When 0<x<0.5, the lithium ions can be found in the tetrahedral sites; when the ratio is increased and 0.5<x<1, they will occupy the octahedral sites. The following diagram are the voltage curves for lithium-ion insertion and extraction from Li2xMn2O4:

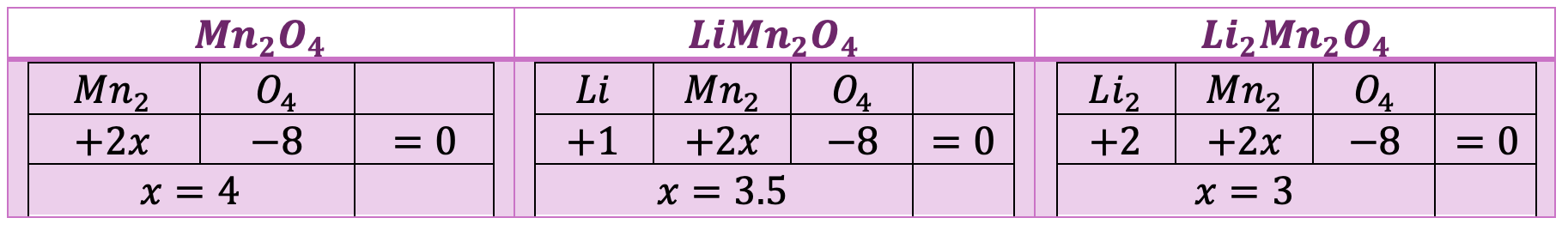

It now becomes evident that there are three species that exist while this material is being cycled (i.e., when lithium ions are being inserted during discharge and de-inserted during charge). The next aspect to consider are the charges of the manganese ion in each of these compounds. The following table illustrates these calculations:

In its fully discharged, lithiated state as Li2Mn2O4, the spinel structure would, theoretically, be able to store a very large amount of lithium ions in its numerous octahedral sites, where the lithium ion sits very comfortably. However, this is not done due to the inherent issues of the manganese ion with a 3+ charge.

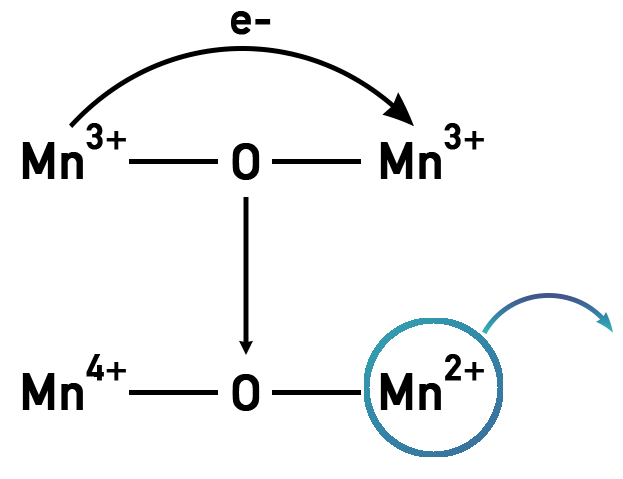

When the battery is fully charged (implying all the lithium ions are in the negative electrode), there is a mix of 50% Mn 3+ ions and Mn 4+ ions in the form of . As it begins to discharge, all the Mn 4+ ions reduce and become Mn 3+. The probability of two Mn 3+ ions connected to an oxygen then becomes very high, and this results in the donation of an electron to the adjacent Mn 3+ ions, as illustrated below. The ensuing molecule would then have an Mn 4+ ion and an Mn 2+ ion.

Manganese ions with a 2+ charge have a propensity to irreversibly dissolve into the electrolyte (as the previous diagram demonstrates), meaning rapid loss of active material.

On the other hand, a manganese ion with 3+ in the octahedral coordination will elongate its atomic orbitals along one axis and contract them along the other two. This decreases the symmetry of the molecule by distorting the octahedrals, which leads to significant volume changes and the cracking of the electrode. This behaviour is known as a cooperative Jahn-Teller distortion. In the manganese spinels,

Li2xMn2O4, the concentration of Mn 3+ is already very significant when (essentially when the battery is only halfway cycled) to cause Jahn-Teller distortions at only room temperature.

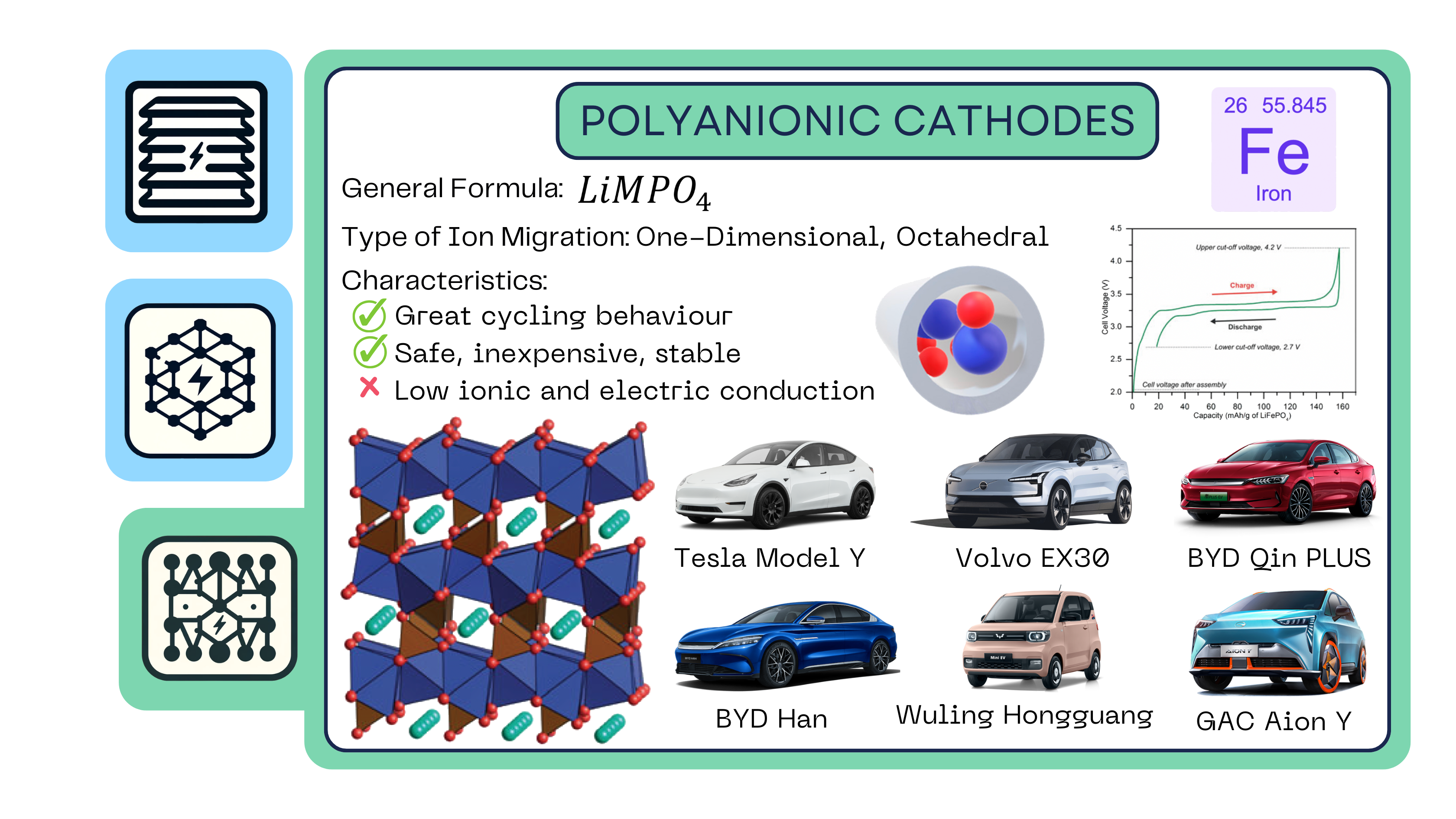

Polyanionic Cathodes

Polyanionic cathodes consist of a hexagonal array of cations with the transition metal sitting in an octahedral. The octahedral are corner-linked to one another in chains that are organized into layers – but not connected between the layers. The layers of the corner-lined octahedrals are bridged by a phosphorus, which sits in the tetrahedral interstitials.

The phosphorus has a +5-charge state, meaning it forms a very strong bond to the oxygens around it. Now, there is an empty interstitial between the PO3-4 tetrahedral. Again, given the +5 charge of the phosphorus, the repulsion felt by the lithium ion is enormous, meaning it cannot move between the chains. This means the lithium can only move in one-dimension.

The metal in most polyanionic cathodes is iron. Iron was initially not considered as an attractive material for positive electrodes because it has a very low potential (less than 2V). However, when the bond between the iron and the anion is more ionic rather than covalent, the potential can increase significantly.

This is known as the induction effect, and this allowed for the exploration of iron as a cathode material. Nonetheless, given this tightly packed structure, compared to the other chemistries, the ionic diffusion as well as the electronic conductivity is very low. However, the oxygen is so tightly securely bonded within the structure that there is no risk of it being released. This characteristic makes polyanionic materials cheaper, safer, and much more stable than any of its counterparts.

Summary