An ideal positive electrode will allow for the maximum insertion and de-insertion of lithium ions during each cycle, ensuring high capacity and long-term durability of the battery. To achieve this, the electrode material must possess a high specific energy to store more power per unit weight, coupled with excellent electrical conductivity to facilitate fast charging and discharging. Additionally, the structural integrity of the electrode should remain stable during the repeated swelling and shrinking that occurs with lithium-ion flux. Thermal stability is also paramount to prevent thermal runaway and ensure safe operation under various environmental conditions. These requirements guide the development of advanced materials and technologies aimed at enhancing the performance and safety of lithium-ion batteries:

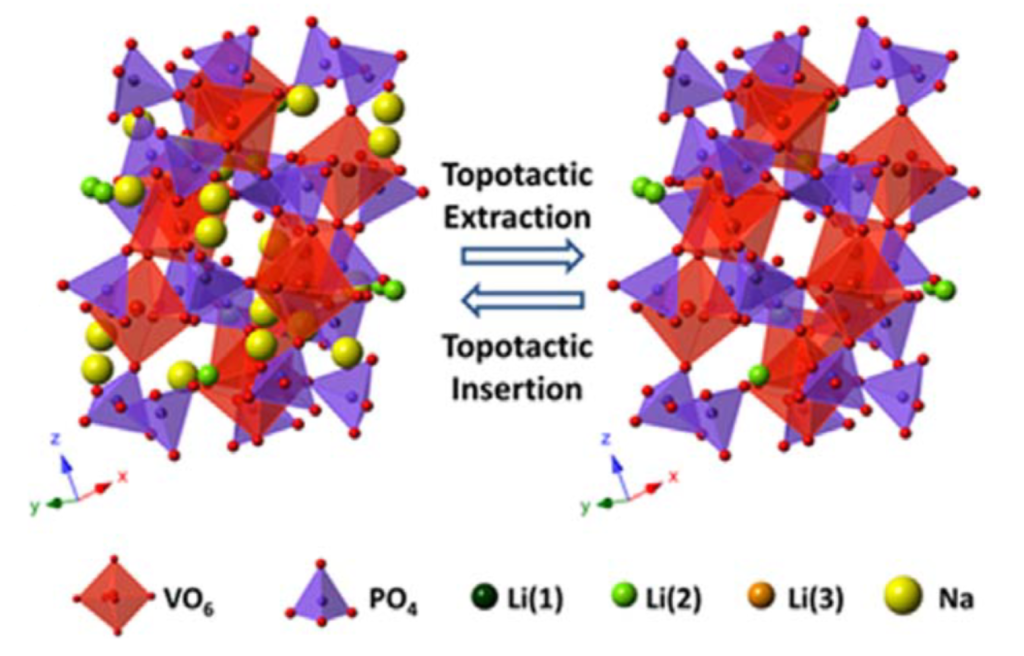

Reversible Topotactic Reactions: When the battery is cycling, ions will enter and exit the electrodes, and this of course leads to structural changes within the battery. An excellent electrode will have minimal structural changes and minimal volumetric alterations while this is occurring. The following figure illustrates this more clearly:

In this cathode (which is part of a sodium-ion battery), the structure has remained virtually unchanged while the sodium ions enter and exit it. However, if the structure grows or shrinks significantly as a result of the insertion and extraction of the cations, it will be prone to cracking or breaking. An electrode that breaks will result in the loss of active material (parts of the electrode might dissolve in the electrolyte), loss of conductivity and capacity, for the electrode will lose contact with the current collector, amongst several other risks. Non-topotactic electrodes present a very high risk to batteries and are often one of the biggest characteristics that are prioritized for good battery performance.

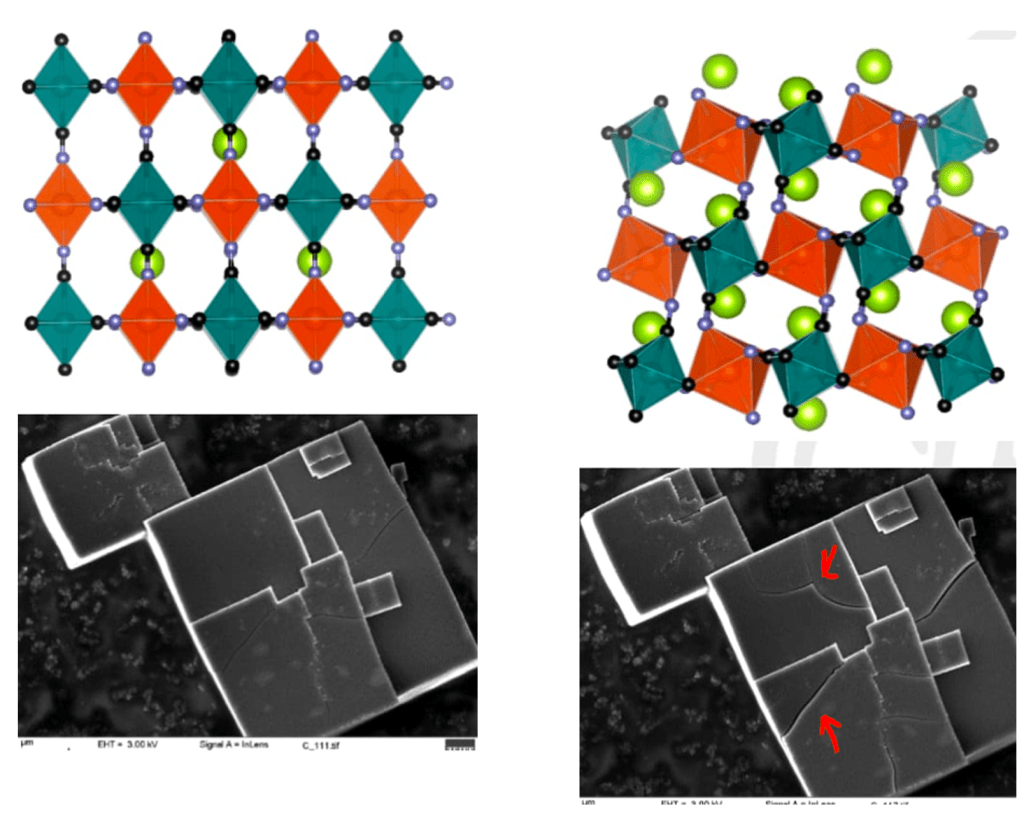

The following diagrams show a non-topotactic electrode cracking after sodium-ions have been inserted (right).

To summarize, electrodes should be able to accept and relinquish cations whilst preserving their original structure.

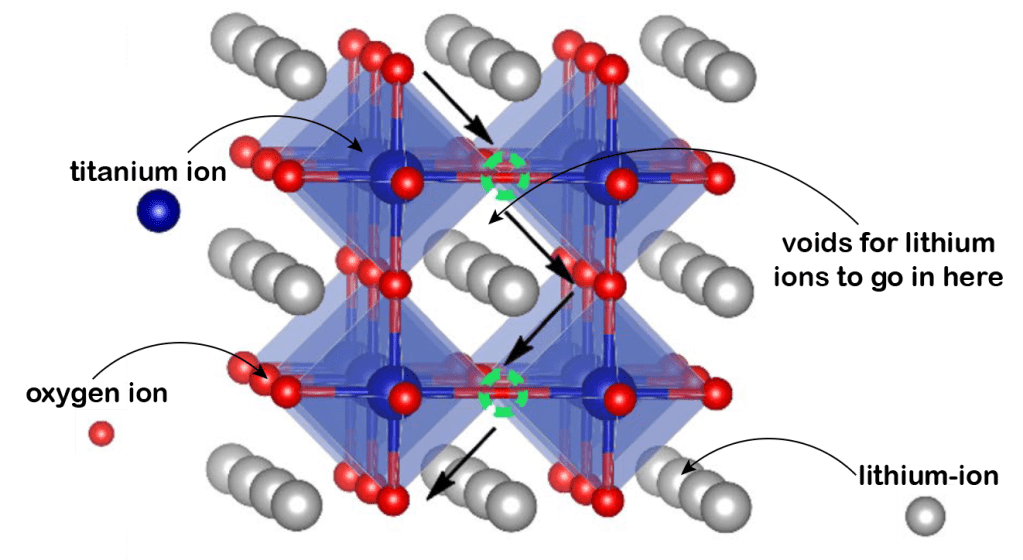

High storage capacity: For lithium-ion batteries, high storage capacity in positive electrodes is essential for enhancing overall energy density. This capacity is determined by the amount of lithium ions that the electrode material can host during the battery’s discharge (lithiation) and charge (delithiation) cycles. A material’s ability to accommodate a high concentration of lithium ions is facilitated by its structure, which should feature multiple voids and redox centers to allow easy ingress and egress of electrons and ions. Consider the example of a perovskite structure utilizing titanium (Ti) as the transition metal:

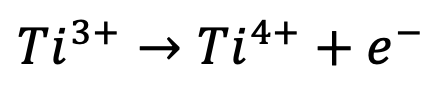

With this structure, the redox reaction that takes place is the following:

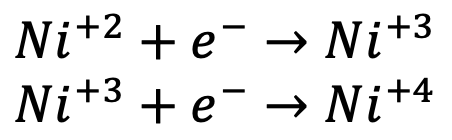

In this reaction, each titanium ion undergoes a change from a 3+ to a 4+ charge, releasing one electron in the process. This type of reaction, where the oxidation state changes by one, is termed a one-electron process. Other metals used in positive electrodes, such as nickel (Ni), can undergo more complex reactions involving multiple electron processes, significantly enhancing the capacity:

Nickel is a metal that can undergo a two-electron process, and each electron contributes to the total capacity of the electrode. To conclude, a higher capacity is determined by a high number of voids for the electrons to travel across and the number of redox centers available.

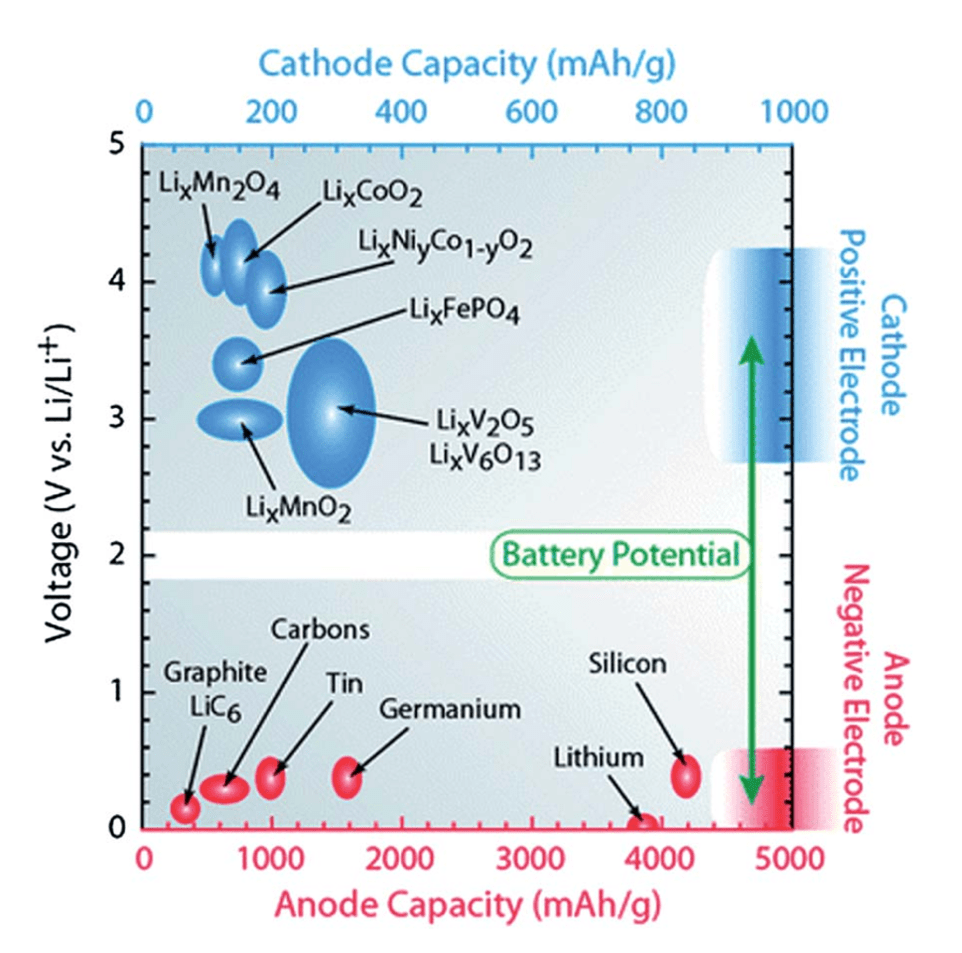

High Reaction Potential: The reaction potential refers to the voltage difference an electrode can achieve relative to the lithium/lithium-ion reference electrode during charge and discharge. For the positive electrode (cathode), a high reaction potential is especially desirable, since it directly increases the overall cell voltage and thus the energy density of the battery (energy density ≈ capacity × voltage). As shown in the figure, cathode materials such as layered oxides (LiCoO₂, LiNiₓCo₁₋ᵧO₂) and polyanionic compounds (LiFePO₄) operate at higher voltages, while anode materials like graphite or silicon lie closer to 0 V. The specific reaction potential of each material is dictated by its intrinsic redox couple and local electronic structure, which govern how easily lithium ions and electrons can be inserted or extracted.

High Electronic Conductivity: To maximize the electronic conductivity in a positive electrode, especially in lithium-ion batteries, several effective strategies can be implemented. Firstly, integrating conductive additives like carbon black or graphene is crucial as these materials create a conductive network within the electrode, facilitating rapid electron movement which enhances charge and discharge rates. Secondly, optimizing the particle size of the active material can also improve conductivity; smaller particles provide a shorter path for electron transport, leading to a more efficient conductive pathway.

Additionally, coating the active material particles with a thin layer of conductive materials such as carbon or metal oxides can significantly boost surface conductivity, effectively bridging gaps between particles. Another approach is doping the cathode materials with elements that increase the number of free charge carriers, such as titanium or aluminum. Finally, designing the electrode with a structured architecture, like interconnected fibers or layers, can minimize internal resistance by providing a continuous path for electron flow.

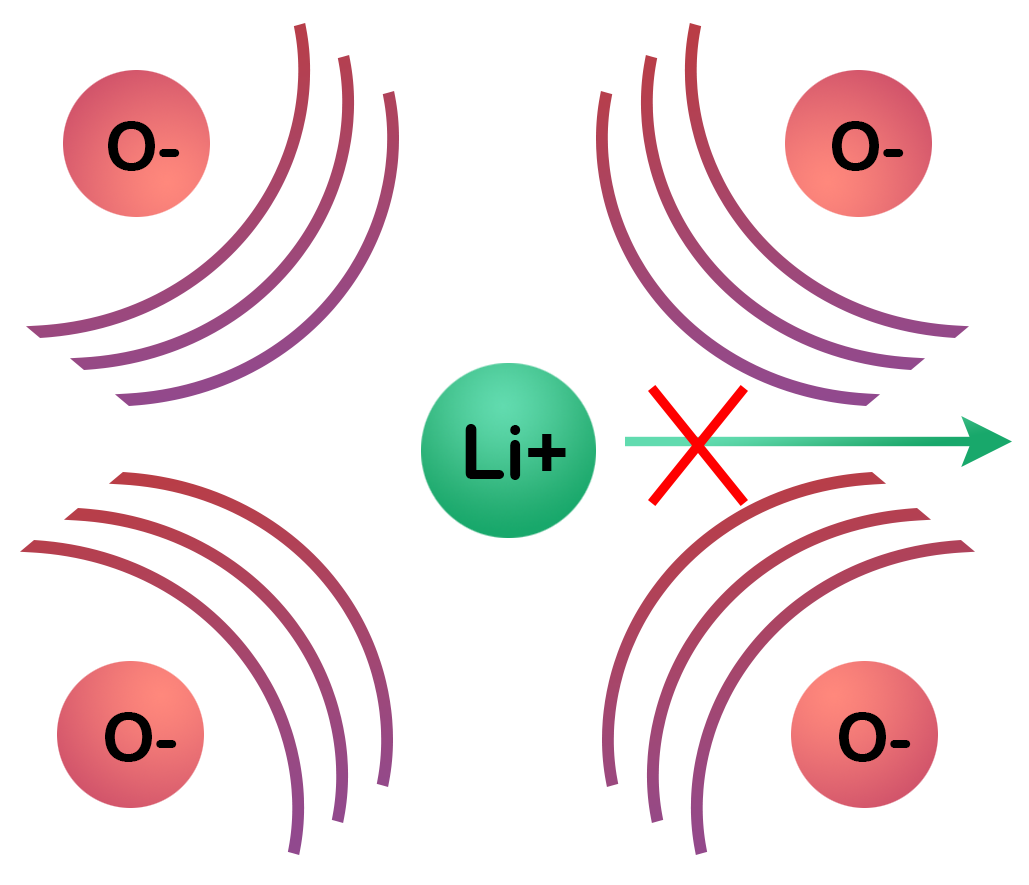

High Ionic Conductivity: Positive electrodes must allow for seamless and easy transport of ions. This task is optimized by minimizing two particularly challenging effects, known as bottlenecking and ion pining:

Bottlenecks: These occur when the migrating ion must pass through a constricted region in the crystal lattice, often defined by the spacing between adjacent anions (such as oxygen). If two oxygen ions are positioned too close together, their strong electrostatic repulsion creates a narrow passage. This constriction increases the migration barrier the lithium ion must overcome, effectively inhibiting its movement. The width and geometry of such bottlenecks are therefore critical descriptors of a material’s ionic conductivity, since they directly determine how easily lithium can hop from one coordination site to the next.

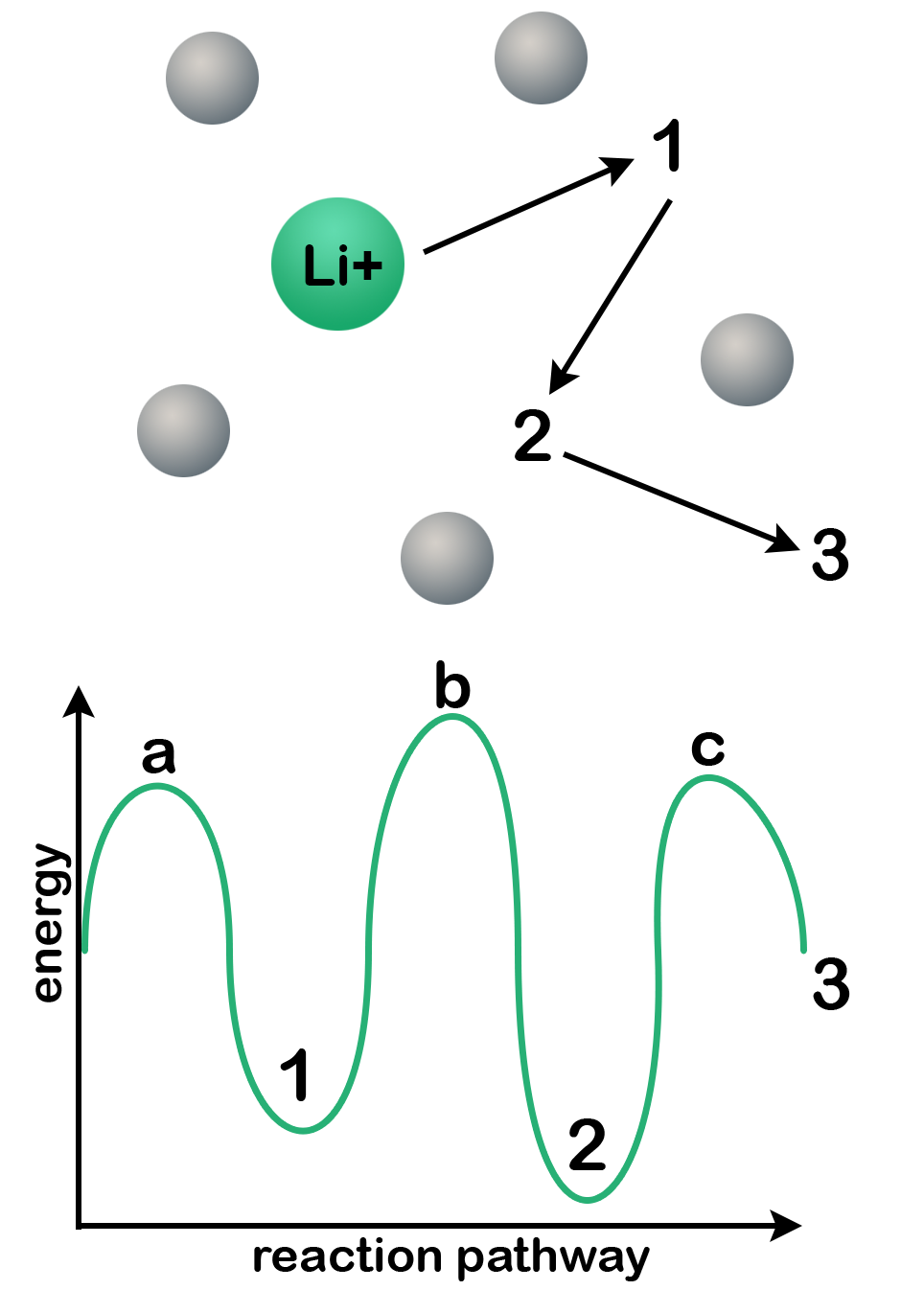

Ion pinning: Observe the following diagram. When a lithium ion migrates through a solid lattice from site 1 to site 2 to site 3, it encounters different coordination environments along its path. At site 1, the ion occupies a stable position corresponding to an energy minimum. This state is often described as a potential well. To move forward, the ion must overcome activation barriers at the adjacent saddle points (labeled a and b) before reaching the next stable site. These barriers represent the energy required for the ion to hop from one coordination site to the next, and their height determines the ease—or difficulty—of lithium transport through the material.

Low cost, safe, environmentally benign: The materials that compose the electrode must not be too expensive, must not be hazardous to human health, and should not present environmental harm or risk.