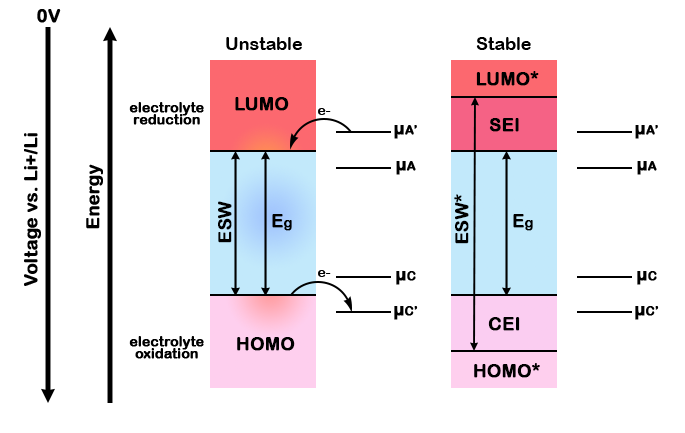

When a freshly created battery is cycled for the first time, a series of spontaneous reactions take place. Given that the anode is set to operate at very low potentials, a decomposition occurs between the electrode and the electrolyte. This can be better envisioned with the following diagram:

muA and muC represent the redox potentials of the anode and the cathode, respectively while phiA and phiC represent the work functions of each electrode. ESW represents the electrochemical window of stability of the electrolyte, which refers to the voltage range within which the electrolyte remains chemically stable and does not undergo decomposition. However, when the voltage drops below this window at the anode’s surface, the electrolyte components undergo reduction reactions because their redox potential is higher than the potential of the anode at this moment. As can be observed in the diagram, when the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) of the electrolyte is lower than the redox potential of the anode, the electrolyte will be reduced. Likewise, if the highest unoccupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of the electrolyte is higher than the redox potential of the cathode, the electrolyte will be oxidized.

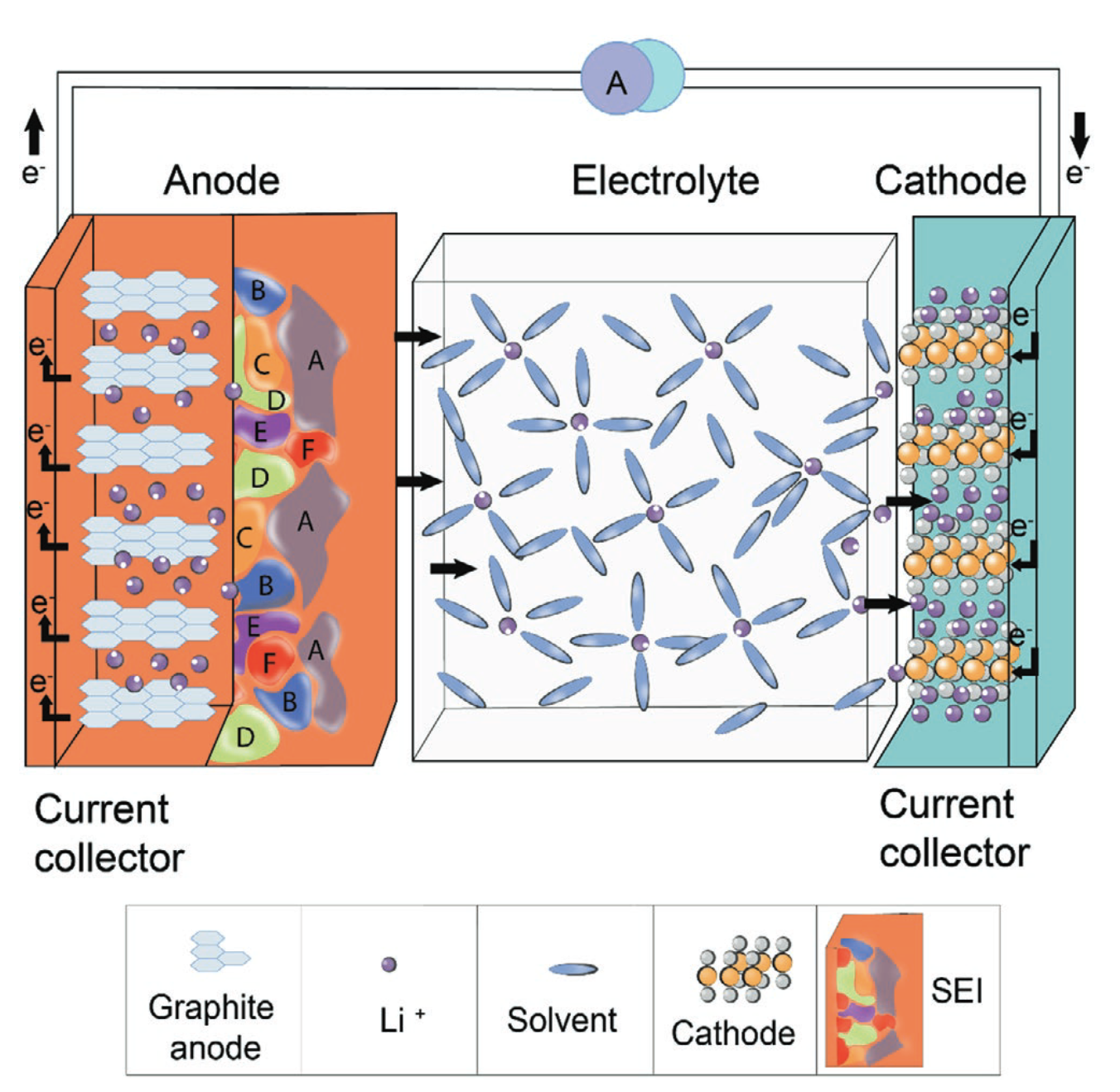

These reduction reactions result in the decomposition of electrolyte components, leading to the formation of a complex, mostly ionically conductive layer on the anode’s surface—this is the SEI layer. The SEI layer is critical for battery performance for several reasons. Firstly, it acts as a physical barrier that prevents further direct contact between the anode and the electrolyte, thereby substantially reducing further decomposition of the electrolyte. This prolongs the electrolyte’s life and, by extension, the overall battery’s life. Secondly, while it prevents electrons from directly interacting with the electrolyte, it allows lithium ions to pass through. This selectivity ensures that lithium-ion intercalation and de-intercalation can continue to occur at the anode, which is essential for the battery to charge and discharge.

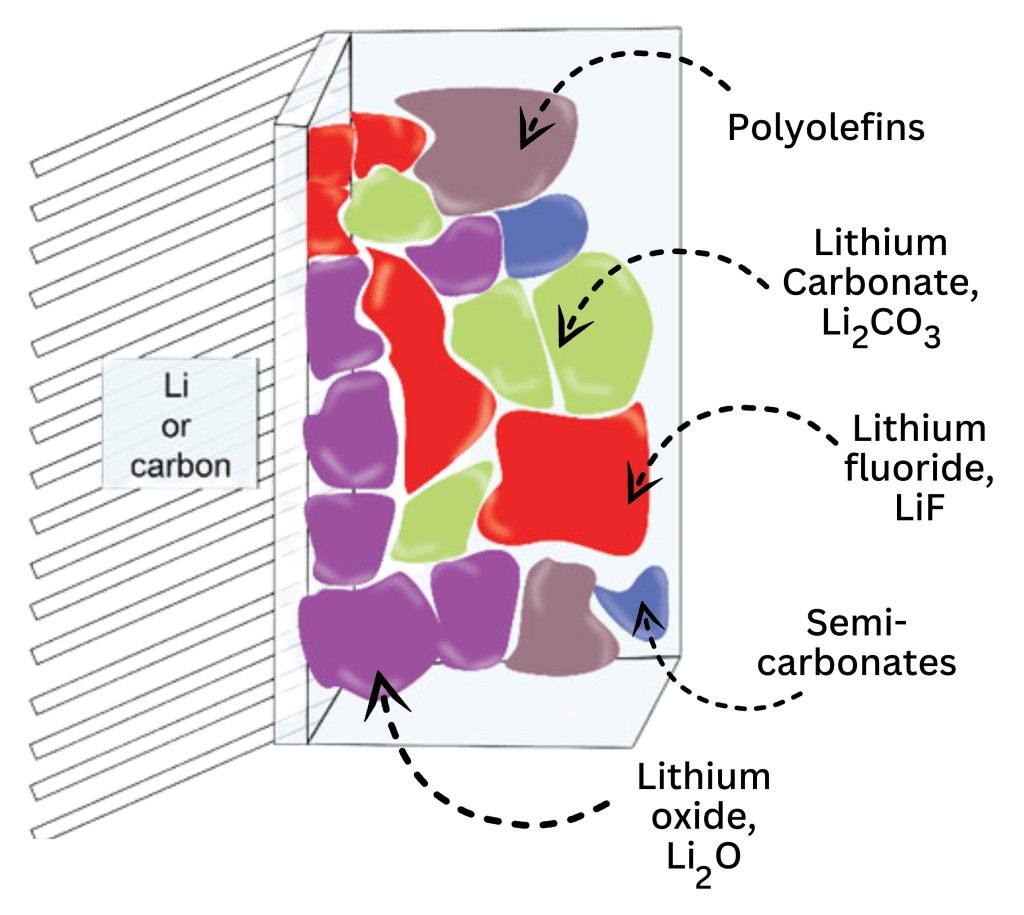

A close-up of the SEI can be seen below:

These figures demonstrates how the SEI forms on the surface of the anode. The inner layer that is closest to the electrode is inorganic (normally made out of Li2CO3, LiF, and Li2O), which allows lithium-ion transportation. The outer layer that is in contact with the electrolyte is comprised of organic materials (these compounds are made out of lithium and the type of solvent used in the electrolyte, which is generally ethylene carbonate), and these provide structural strength and flexibility to the layer, accommodating for the volume changes that occur on the anode when the battery is cycling.

However, the formation of the SEI layer is a delicate balance. If the SEI layer is too thick, it can impede the movement of lithium ions, reducing the battery’s efficiency and capacity. Conversely, if it is too thin or incomplete and not uniform, it may not effectively prevent the electrolyte decomposition, leading to rapid degradation of the battery.

As an aside, although the previous graph also implies the existence of a passivation layer forming on the cathode (the cathode electrolyte interface, CEI), this layer is normally much thinner than the SEI and has less impact on battery performance than the SEI, given that the electrolyte is quite stable at the operating potentials for the cathode and higher potentials are most often required to significantly oxidize the electrolyte. For this reason, this investigation will not focus on the CEI layer, but rather, only on its anodic counterpart – more specifically, on the effects the SEI has on battery performance.