Primary and Secondary Batteries

Primary batteries, also known as disposable batteries, are designed to be used once until they are depleted, and then disposed of. They cannot be recharged in a safe or effective manner. These batteries are made with chemical reactions that are intended to be irreversible, meaning once the chemical energy is converted into electrical energy, the process cannot be efficiently reversed. Primary batteries tend to have a long shelf life and a relatively constant voltage output until exhausted. In terms of battery chemistry, they can also be referred to as galvanic or voltaic cells, where the chemical reaction is designed to be one-directional and non-reversible, meaning once the reactants are depleted, the battery cannot produce electricity anymore and is discarded.

Secondary batteries, on the other hand, are rechargeable batteries that can be used, recharged, and used again multiple times. This capability is due to their chemical reactions being reversible. The cycling of the battery can be repeated many times, making secondary batteries more economical and environmentally friendly over the long term, despite their higher initial cost.

In terms of battery chemistry primary batteries also be referred to as galvanic or voltaic cells, where the chemical reaction is designed to be one-directional and non-reversible, meaning once the reactants are depleted, the battery cannot produce electricity anymore and is discarded.

In contrast with galvanic cells, electrolytic cells use electrical energy to drive non-spontaneous chemical reactions. This process is known as electrolysis. Electrolytic cells require an external power source to induce the chemical reaction, which reverses the direction of electron flow compared to a galvanic cell. Secondary batteries operate on the principle of electrolytic cells when they are being recharged: by applying an external electrical current, the discharged battery is restored to its original chemical state, making it ready for use again. During discharge, secondary batteries function as galvanic cells, converting chemical energy into electrical energy. This investigation will focus exclusively on secondary batteries.

The significance of precise nomenclature cannot be overstated. As was previously mentioned, the charging process of a secondary battery involves a reversal of roles for the anode and cathode relative to the discharge cycle. Specifically, an external power source inverts the current flow direction observed during discharge, transforming the electrode initially serving as the anode (the oxidation site) into the cathode (the reduction site) during charging, and the reverse applies to the cathode. Consequently, the electrode undergoing oxidation (electron loss) now acts as the positive electrode, influenced by the direction of the current from the external power source, while the electrode undergoing reduction (electron gain) assumes the role of the negative electrode.

Despite the dynamic reversal characteristic of secondary batteries, the terms “positive electrode” and “negative electrode” will consistently correspond to the cathode and anode, respectively. This convention aims to maintain clarity and consistency in discussing the electrochemical processes involved.

Voltage, Current, and Resistance

Voltage, often synonymous with potential difference, is defined as the electrochemical reactions that occur at the electrodes. It can be summarized with the following equation:

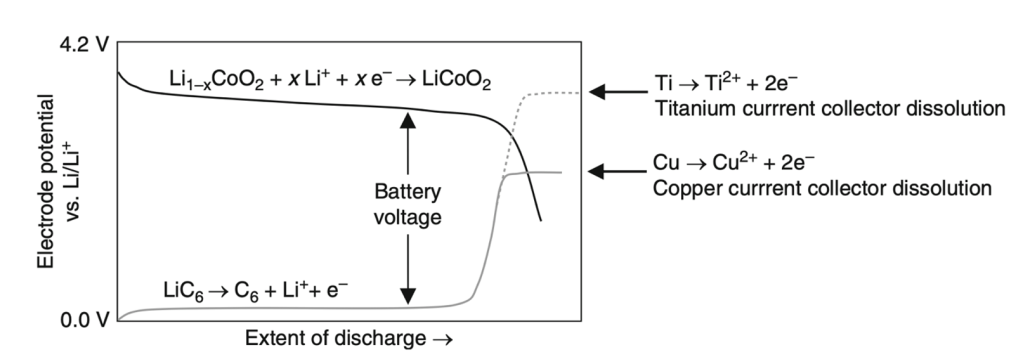

With this equation, it is then evident that the potential of the positive electrode must be maximized while that of the negative electrode must be minimized in order to obtain the largest battery potential. This can be observed clearer in Figure 28, where the upper curve represents the reactions occurring at the positive electrode, and the lower curve, the reactions occurring at the negative electrode:

Indeed, a larger difference between the voltage capacities of each electrode generates a larger battery voltage. A larger battery voltage entails a battery with higher performance.

The reactions that occur at the electrodes give rise to a flow of electrons, known as the current. The current is inhibited by the resistance, the measurement for the opposition of electronic flow. The relationship between these three parameters comes together with Ohm’s Law, which can be summarized below:

Impedance

In battery operations, resistance manifests not only as a simple DC value but more generally as impedance. Impedance (symbol Z) describes the total opposition a circuit presents to an alternating current (AC), which oscillates sinusoidally with a given frequency. Unlike pure resistance, impedance also accounts for frequency-dependent effects arising from capacitive and inductive components within the electrochemical system. In the context of batteries, this means that the pathways for ion migration, charge transfer at electrode–electrolyte interfaces, and double-layer capacitance all contribute to the overall impedance spectrum.

This concept directly relates to polarization phenomena, since the various forms of polarization—ohmic, concentration, and charge-transfer—each introduce characteristic resistive or capacitive elements. These appear as distinct features in impedance measurements (such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy, EIS). In other words, impedance is not just an abstract AC parameter, but a practical tool to probe and decompose the underlying polarization processes that limit battery performance.

Polarization

Polarization refers to the deviation from ideal behavior during electrochemical reactions within the cell. When a battery is being charged or discharged, the ideal scenario is that the voltage responds instantly and linearly to the current flow. However, in real systems, various factors cause the voltage to deviate from this ideal behavior, which is referred to as polarization.

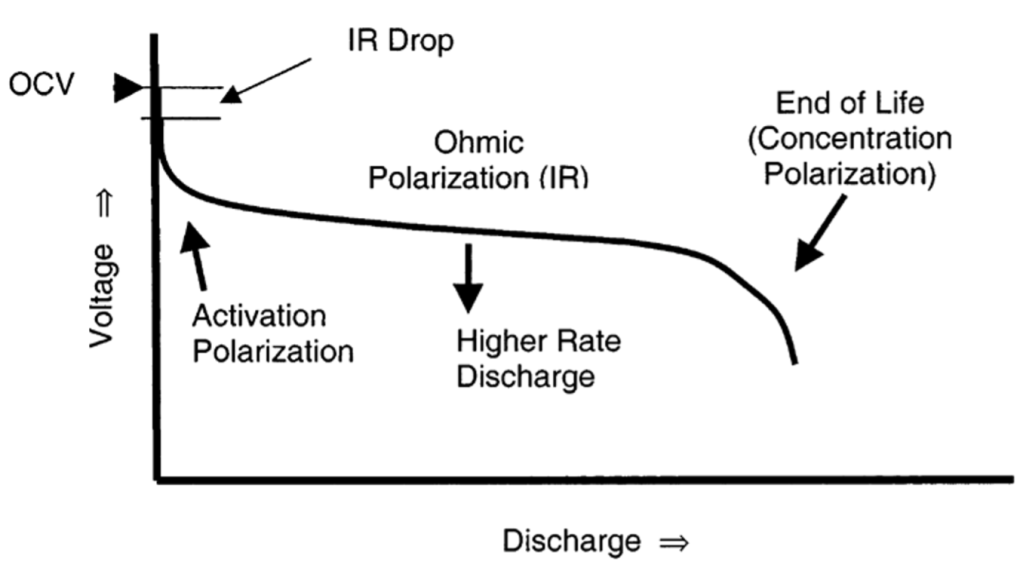

There are several types of polarization that can affect battery performance, which can be observed in the following graph:

- Activation Polarization: This type of polarization is attributed to overcoming the activation energy of chemical reactions. Given this, the polarization occurs due to the sluggishness of the electrochemical reactions at the electrode surfaces. It is particularly evident during the start of charging or discharging when the reactions need to “activate” and overcome the energy barrier for the reaction to proceed.

- Ohmic Polarization: This type of polarization is caused by the internal resistance of the battery to the flow of ions and electrons. It can be modelled using Ohm’s Law, the equation for which can be found in Table 6. It includes the resistance of the electrolyte, electrodes, and any connectors or separators within the battery. Ohmic polarization is often immediately noticeable as a voltage drop when the current is applied, which is also known as an IR drop.

- Concentration Polarization: As a battery is charged or discharged, the concentration of ions near the electrodes can differ from that in the bulk electrolyte, leading to concentration gradients. This difference causes additional potential loss because the electrochemical reactions are limited by the rate at which ions can move through the electrolyte.

Polarization causes the battery to be less efficient. For example, during charging, more energy is required to overcome the polarization effects, and during discharging, less energy is delivered due to voltage drops. Additionally, higher levels of polarization can limit the rate at which the battery can be safely charged or discharged. Rapid charging or discharging can exacerbate polarization, leading to lower usable capacity and higher heat generation. The release of heat (just like the release of sound) is always an indication of irreversible energy loss towards the surroundings, given that the energy is being dissipated as heat, rather than being stored or delivered as electrical energy. Heat release can also lead to thermal management issues.

Over time, the effects of polarization can produce capacity fade, for the repeated inefficiencies and stress on the battery materials will degrade their performance. At high voltage loads, it is also likely for polarization to destabilise the battery voltage, which would of course cause performance issues since a stable voltage is often required. All these factors will eventually contribute to a shortened lifespan for the battery, given that the rate of degradation of the materials will be accentuated by the stress of trying to overcome polarization effects. For these reasons, battery design and material selection should always prioritize the management and reduction of polarization in order to ensure that the battery will deliver a high performance throughout numerous cycles.

Energy

When trying to describe a battery, the term “energy” takes on several definitions. In the first place, it can be denoted as the product between voltage, current, and time. Given the previously established definition for capacity, this equation can also be written as the product between voltage and capacity.

Power

In battery chemistry, power is a measure of the rate at which a battery can convert its stored chemical energy into electrical energy. It is the product between the voltage and the current. Higher power means an engine will be stronger.

Active and Inactive Materials

In battery terminology, the two electrodes are considered active materials, while other components of the battery are denoted as inactive materials. This is given the fact that the conversion of chemical to electrical energy occurs only on the electrodes. The following list summarizes these classifications:

Coulombic Efficiency

There are several ways to measure a battery’s efficiency. A very common measurement is the Coulombic efficiency, which denotes the ratio between the charge that goes inside the battery and the charge that it can deliver. An ideal battery has a Coulombic efficiency of 100%, but due to losses caused by polarization, this is often not the case.

The specific energy and power density of a battery are two critical parameters to describe battery technologies. Energy density refers to the amount of energy a system can store per unit mass or volume. On the other hand, power density is a measure of how quickly a system can receive and deliver energy, per unit mass or volume. An ideal device should be able to store as much energy as possible and deliver it at a very rapid rate. In this context, it becomes obvious how both must be maximized, but how doing so is paradoxical. There is an intrinsic trade-off between being able to store large amounts of energy whilst also being able to deliver it as quickly as possible.