Articles about electric vehicles will often mention words like “NMC”, “NCA”, or “LFP” batteries or some three-letter-variant thereof, sometimes followed by a combination of three numbers. Beyond vaguely explaining that these letters denote compositions of some sort, they never really elaborate on what these denominations actually mean – and understanding how these battery types differ from one another is vital for anything related to EVs. Thankfully, in this section, we’re going to tackle this problem head on and understand exactly how electric vehicle battery types are classified.

To begin with this endeavor, we have to go back a bit and remember what we learned about positive electrodes, or cathodes. Let’s go back specifically to the part about layered cathodes and recall how they work (not the whole geometrical spiel, just the bit about intercalation and de-intercalation part).

We’ll now continue by discussing a very common type of layered cathode, lithium cobalt oxide, or LiCoO2. As the name implies, this cathode is a mixture of three elements: lithium, cobalt, and oxygen. Pretty straightforward, right?

Lithium cobalt oxide has a very high theoretical capacity (approximately 280 mAh/g), but it comes with its set of problems: in terms of structure, there is an inherent issue with the transition metal, cobalt. Cobalt tends to dissolve into the electrolyte because it can swap places with the lithium ion. The high mobility of this metal is due to the nature of its bonding with the oxygen. Now, cobalt ions act as bricks that hold the cathode together. Try to imagine if these bricks started to suddenly dissolve away into the electrolyte. The cathode would crumble and fall apart, just like a house made out of bricks would.

So, alright. Maybe this mixture with cobalt wasn’t great. Let’s just quickly glance at the periodic table: cobalt has an atomic number of 26, and the element immediately after is nickel, at 27. Why not try a mixture with nickel?

And thus, lithium nickel oxide, LiNiO2, was born. And thank the heavens it was! Nickel is an amazing metal. It’s much cheaper than cobalt and the redox capacity of the nickel is higher, meaning the electrode would have a higher energy and power density – and let’s be honest, the fact that it doesn’t come with cobalt’s negative PR certainly helps. There is one (literally) tiny problem though…

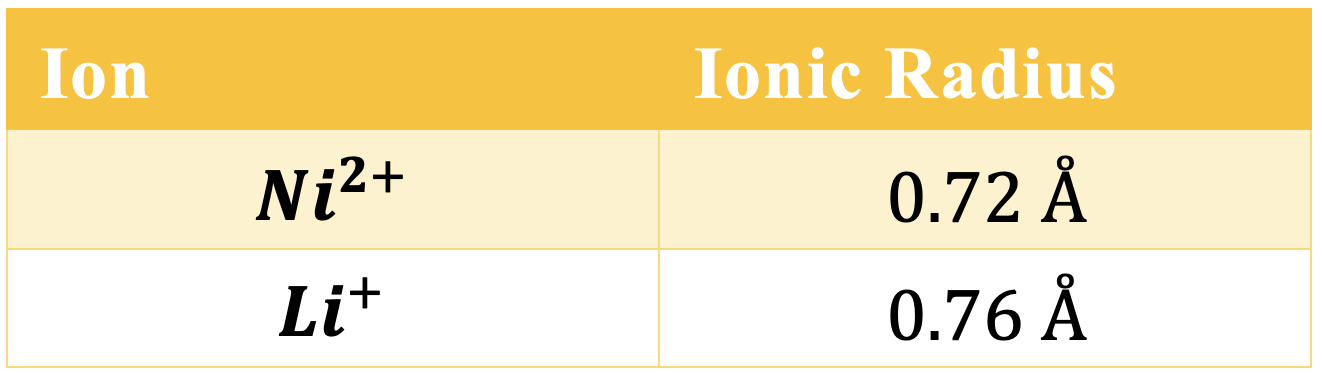

As you can see in the previous table, the nickel and lithium ions have a very similar radius. For this reason, nickel ions are prone to swapping places with the lithium ions during cycling of the battery – a problem we encountered earlier with cobalt, but in much larger proportions. Therefore, pure LiNiO2 has a very slow cycling life before it dissolves into the electrolyte.

Our mixture with nickel wasn’t too successful, so let’s go back to the periodic table. A very close neighbor of nickel is manganese, with an atomic number of 25. Manganese is a fantastic element by all means – if you browse the “Building Blocks for an EV” section, you’ll see manganese exists in copious – nay, luxuriant amounts in our planet. Manganese also has lower levels of toxicity than its predecessors! But, if you quickly go back to the section about Types of Cathodes and just re-read the part about “Problems with Spinel Cathodes”, you’ll remember that manganese is Jahn-Teller active. We don’t have to go into detail about what that means (although I’d certainly love to), but it basically boils down to this: manganese is very unstable in a mixture such as this one, and it won’t take long for it to dissolve into the electrolyte and for the cathode to break down.

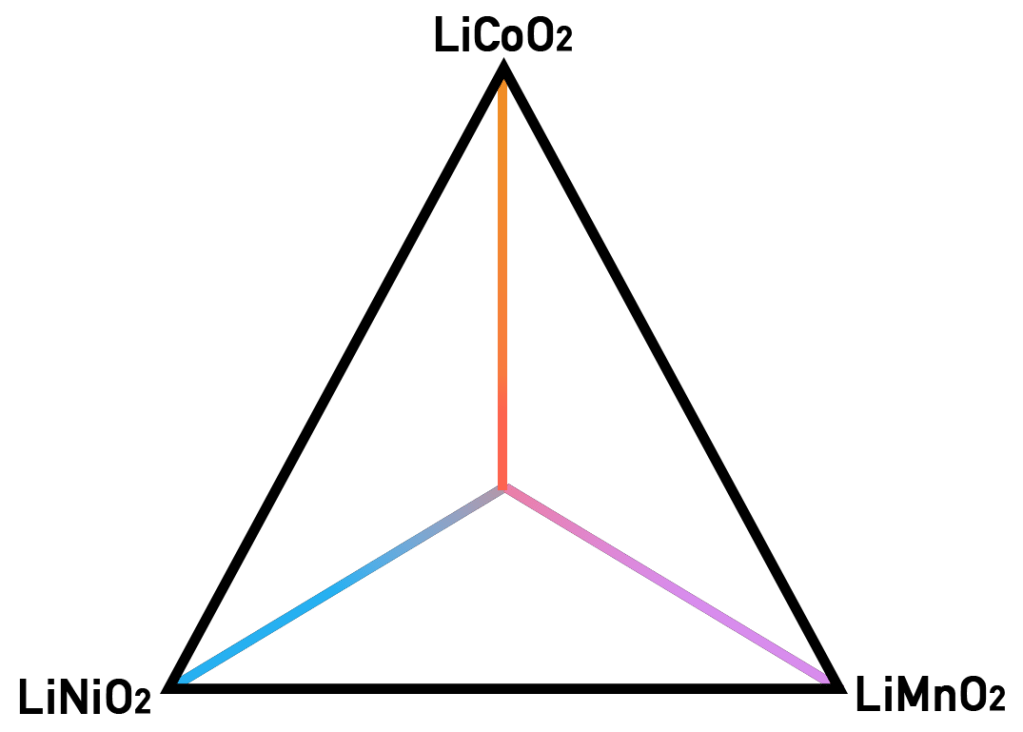

We’ve cycled (get it? Cycled… Like a battery, haha) through most of the important and abundant transition metals and we still haven’t found an ideal one. But to find a solution, adding more dimensions to the problem might help. By this I mean that, you can take all three of our previous mixtures and create a phase diagram with them, placing each at every corner:

Phase diagrams are used in a variety of fields to show the stable phases of a material system under different conditions of temperature, pressure, and/or composition. In this case, our phase diagram will solely be a representation of composition. This means that if you position yourself on the LiMnO2 vertex, your mixture will only have manganese in it (or 100% manganese). If you move towards the LiCoO2 end and stop right in the middle between both vertices, your mixture will be half cobalt, half manganese. And if you want to add nickel to your mixture, then just move to the left, somewhere closer to the LiNiO2 vertex. If you want an equimolar mixture (i.e., the quantities of all elements is the same), just stand in the middle of the diagram – where all three lines intersect!

A great advantage of this method is that, because all these three compounds are layered structures, everything inside the triangle will also be a layered structure. This means that all the mixtures, no matter what their proportions or compositions are, will behave in the same way a layered cathode would, with the same type of intercalation/de-intercalation mechanisms and the same two-dimensional lithium-ion diffusion pathway.

Indeed, this is where research progressed: the three transition metals were now being mixed together so that one metal’s shortcoming could be overcome by the other two, and viceversa.

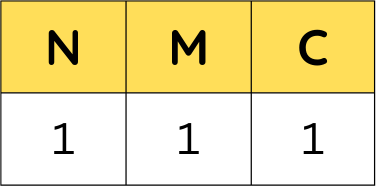

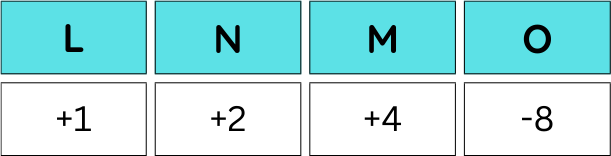

The first composition that was experimented with was with the one right in the middle: equal amounts of nickel, manganese, and cobalt, which can also be written as Ni:1, Mn:1, Co:1. Or in much organized and cleaner terms:

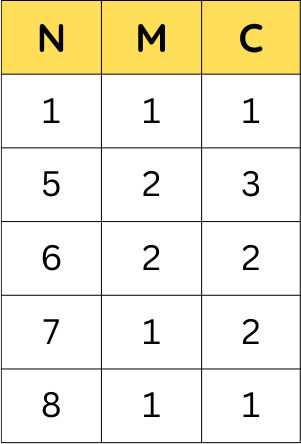

So as you can see, this is where the nomenclature comes from! Sometimes authors will change the order and write NCM rather than NMC, but idea remains the same. As for the numbers that follow, each number represents the proportion of each element in the mixture.

NMC111 proved to be an excellent cathodic material and it is still widely used. Let’s try to understand why:

Remember how manganese ions, Mn+4, would reduce into Mn+3 and Mn+2 ions as the battery was discharging? Well, Mn+3 was structurally unstable and would thus, collapse (the consequences of being Jahn-Teller active) and Mn+2 would dissolve into the electrolyte, leaving us with pretty much a broken cathode. Well, that’s where the nickel comes to the rescue: the nickel becomes the main redox-active element in the mixture, as in, the only metal to reduce and oxidize during the cycling process, and thus, keeping the manganese in its happy and stable 4+ charge.

This in turn stabilizes nickel from reducing too far into its 2+ charge, which switches places with the lithium ions. Nickel’s generous range of accessible redox states enable it to take charge (get it… take charge, cause it’s a battery) of the voltage changes during the battery’s operation, while manganese and cobalt are the pillars that keep the structure from collapsing (and the nickel from reducing too much).

The performance of NMC 111 prompted more research towards more blends.

NMC 811 appears to be an industry favorite, since it provides a very high potential of 4V, provides a very high capacity of approximately 200 to 220 mAh/g, and additionally, has a very high energy density, of approximately 800 Wh/kg.

Another blend with great potential involves aluminium instead of manganese. The cathode in this case is known as NCA. EVs with NCA batteries are not very common outside of the realm of high-performance vehicles, but they’re certainly intriguing and full of potential (I’ll stop with the puns now).

Aluminium provides a structural advantage in the sense that it can sit in the lithium sites and act as a pillar that holds the layers together. The aluminium ion is also in the 3+ charge state, which forces the cobalt ion to remain in the 3+ state as well, the desired and most stable charge for cobalt. NCA has a very high practical capacity of approximately 200 mAh/g.

There are even more esoteric mixtures that are still being investigated. For example, there’s LixNi0.5Mn1.5O4, a spinel cathode. When it’s cycled, the electronic charges of each species are as follows:

The same theory as earlier applies: the nickel gets oxidized rather than the manganese, allowing the manganese to remain in the 4+ charge. This type of blend is particularly promising because the quantity of manganese can be maximized without any trepidation of active material loss. This is because nickel has three accessible redox states, meaning that it can carry all the redox processes without the manganese ever needing to be involved. And again, given that nickel has such a high redox potential, the potential of the battery can be kept well above the potential where manganese is active.

This is a particularly interesting blend since it consists of a spinel cathode – meaning three-dimensional channels for the lithium-ion diffusion!

The final bit left to be explained is the name for polyanionic cathodes. This part is extremely straightforward. From our cathodes article, you’ve learned that there’s only one type of polyanionic cathode: the lithium iron phosphate one. Well, iron is Fe, phosphorus is P. There you have it! LFP.